The phrase “Is there a doctor in the house?” originally comes from the theater world: if an audience member fell ill, the stage manager would yell out for any possible immediate medical assistance from the “house”, i.e., the audience section of the theater.

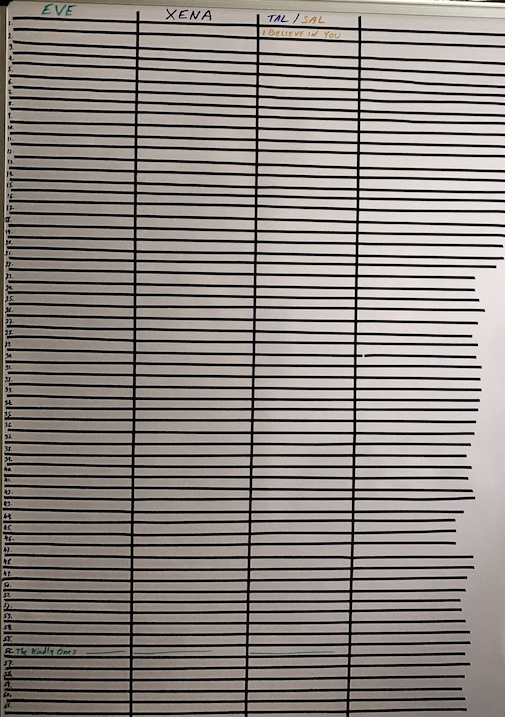

Both Xena Warrior Podcast and Xena Warrior Business reviewed Xena Warrior Princess’s first season finale, Is There a Doctor in the House? and they both thought the episode was an odd choice for a season-ender. Why not end the first season with Callisto, with its introduction of Xena’s key foil, or Death Mask, with a plot that offered a logical book-end to the first episode by showing the man responsible for Xena’s dark path? Instead, we have an episode about healing, slightly silly guest shots of famous Greek physicians, a grotesque centaur baby, and the highly coincidental return of Amazon Ephiny out of the blue, in a seemingly haphazard plot turn from the previous two episodes. Both podcasts explain the apparent arbitrariness of this episode by pointing out that it originally was to have aired earlier, but due to editing issues, was postponed until the end.

No doubt, and in terms of story arcs, it does seem to be a left turn, but I think this is a more appropriate book-end for the first season when you take into account its “logic of aesthetics”, as Rob calls his storytelling method. Let’s take a closer look at this episode’s ingredients and where they came from, and see how it wraps up the first season using poetry, not prose.

First, a reminder: I’m not trying to build a case for some hidden meaning in the show; we can all see what it means. But the way it’s told, it’s “aesthetics”, as I’ve describe it, is not always so apparent. Allow me to repeat these three points from the last essay, about the show’s process:

- Rob Tapert has stated that he used Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths as his unofficial show bible, and that the Xena staff was asked to be familiar with it as well. Graves believed that what we now know as Greek myth is actually the misunderstood remnants of an ancient matriarchal society whose history is now lost. This gave the show’s creative team a unified take on the myths they selected and how they were used.

- Rob played a large role in the shaping of each episode; along with show runner R.J. Stewart, they came up with 90% of the episode ideas, and Rob often supplied a brief summary of each episode for the writing staff. He also supplied reference materials for each episode, including books and videotapes. This approach allowed for the possibility of a consistent aesthetic language to be developed and managed, regardless of who wrote the teleplay.

- Showrunner R.J. Stewart, like Rob Tapert and Sam Raimi, is a writer experienced in using references and templates from movies, tv, and literature as a basis for his stories. He was story editor on Remington Steele, a show that shaped each episode around a classic Hollywood movie (since the main character was an actor posing as a detective). R.J. also grew up in Greece, and is familiar with Greek myth and theater, and used Greek plays as often as Greek myth on the show. He either wrote the teleplays, rewrote them, or gave extensive notes on all of them before they went to final draft.

Where does this episode take place?

We’re told Xena and Gaberielle are in a forest between Thessaly & Athens:

“Maybe we should take the southern route,” Gabrielle asks. “This is the shortest way to Athens” says Xena. “This forest is the only way between Thessaly and Mitoa. Whoever controls it controls—“. Xena is interrupted. Was she going to say “the route to Athens”?

Probably few of us worried about the details of this exchange. It sounds vaguely urgent, without explaining why, and before we start to get really curious, they’re interrupted. Chris Sims of Xena Warrior Business actually tried looking up this information, and made what I thought was a revealing discovery: according to Google Maps, when you ask it for directions from Thessaly to Athens, you get a path from Thessaly in the U.S., to Athens in Greece. That’s because there is no Thessaly in Greece, in terms of an address of any kind. Thessaly is, and was, a region, not a town. It covers much of northern Greece. So where is Mitoa? Again, you will not find it on a map, because there is no such place, anywhere. Alison Stock of the same podcast accidentally refers to it as Minoa at one point, which is probably what the writers based the name on (Minoa was a Trojan-era settlement in Crete, nowhere near this area). This raises another question: why make up a name? Why not just pick some southern town facing Thessaly en route to Athens, like, say, Corinth? Or a region, like Sparta? After all, we’re never really told anything about Mitoa specifically that would contradict our knowledge of any other town.

I think the reason why is that, like Thessaly, Mitoa is also a region, not a town. We know that Euripides was a strong influence for R.J. Stewart, and the subtext of Euripides’ plays was the Peloponnesian War: he wrote about the Trojan War, but he actually lived through the Greek civil war, which is what his plays were really about. This war between Mitoa and Thessaly is also described as a civil war, and I believe this episode is the closest the show ever gets to depicting the Peloponnesian War. We even have a clue that this is the case, when we’re told about a little boy named Piraeus: he never actually appears onscreen, but his name is one of the most famous locations in the Peloponnesian War, the port of Athens. It’s seven miles from Piraeus to Athens, inland, and during the Peloponnesian War this distance was protected by the Long Walls, whose construction was considered by Sparta to be a hostile act. The war ended when Sparta captured Piraeus, and they quickly demolished the Long Walls. This little boy has another significance as well, which I’ll discuss in a moment.

What is this war about?

Gabrielle asks this question as well, and Xena’s answer is cut off. We’ll be told later it’s a religious war, but we only see one religion: the Thessalians’ worship of Asclepius, whose name in English means “unceasingly gentle.” This episode is set in his temple of healing, and it’s odd that his religion would be the cause of all this senseless strife. If we look in Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths, we’ll learn that it’s a bit more complicated than that:

In chapter 50, we learn that Asclepius is from Thessally. His mother, Coronis, was impregnated by Apollo, who killed her when he suspected her of infidelity. Gazing at her corpse, he immediately regretted his action, but did not know how to restore her to life again. He called on Hermes to perform a Caesarean section on Coronis, saving the life of her boy, whom Apollo named Asclepius. He was taken to the cave of Cheiron the Centaur, who taught him the arts of medicine and the chase. He became so skilled in surgery and the use of drugs that he is revered as the founder of medicine.

Does this sound familiar? Of course! We have here the main ingredients of Is There a Doctor in the House?! It’s a perfect fit for a medical drama, by dramatizing the mythic origins of medicine. We can see the inspiration for Gabrielle’s being raised from the dead, and the presence of the centaur storyline, including the birth of a centaur by a human, which would necessitate such a procedure. It makes sense, then, that Ephiny would reappear in this episode.

There’s more to this myth: we’re told that Athena made two drugs from Medusa’s blood: one with the power to raise the dead, the other the power to instantly destroy. She gave Asclepius the power to raise the dead, while keeping for herself the power to destroy, and she used it to instigate wars.

Athena is part of the “Greek Subtext” of Xena’s story, and in a way, Xena has her attributes in this story: she’s used her knowledge in the past to destroy, and now uses it to give life. In my previous post, we saw Xena stand in for Athena in the story of Ulysses, and in my next post, we’ll see her do it again, in The Price.

So this is the mythical background for Asclepius, but Robert Graves doesn’t stop there. He provides his own socio-political explanation of the truth behind the myth, which is relevant here. He interprets this myth as a depiction of ecclesiastical politics in northern Greece, an actual religious war between two colleges of healing:

“Apollo’s Hellenic priests were helped by their Magnesian allies the Centaurs, who were hereditary enemies of the Lapiths, to take over a Thessalian crow-oracle, hero and all, expelling the college of Moon Priestesses and suppressing the worship of the goddess. Apollo retained the stolen crow, or raven, as an emblem of divination, but his priests found dream-interpretation a simpler and more effective means of diagnosing their patients’ ailments than the birds enigmatic croaking.”

This is all rather involved, and may seem a bit to esoteric for a Xena episode, but let’s not forget that Rob Tapert was fascinated with religious history, and how religions evolved. Graves’ book lays out an interesting way to basically dramatize Greek myth without having to rely solely on its fantastic elements. He has said that Xena relied more on religious history than Greek myth, as Hercules did, and I think this means, in part, that he relied more on Graves’ interpretations of myth. In this case, the idea of a religious war, as opposed to merely depicting a battle between the gods.

You might ask: did the writer, a freelancer, do all this research for her one Xena episode? I think it was unnecessary. R.J. Stewart, in a 1999 interview for Cinefantastique, said:

“As far as a freelancer goes, we generally give them the idea. We work and develop the idea with them and then when we get to the point where we think the story is right we send them off to do the script. Some of them hit pretty close so there isn’t a lot of rewriting to do. Others miss by a mile and we have to do a pretty big rewrite. That’s really not much of a reflection on the writer, whether they’re good or not. It’s whether they’re a good marriage to the show.”

Patricia Manney, this episode’s writer, very likely didn’t know the underlying sources involved beyond what was supplied, but I think she was a good fit for this assignment. Her focus as a writer, then and now, are the themes of empathy, healing, and the relation between storytelling and science.

What is this episode about? And does Greek myth play a key role in it?

There are two main themes to Is There a Doctor in the House?: freedom and compassion, and they’re dramatized in the role they play in storytelling and medicine in finding a solution to war.

Galen the priest is trapped in ignorance and fear, and his temple to Asclepius is ground zero of the war between the Thessallians and the Mitoans. He can’t yield to rival dogma, for he has no experience to ground any such compromise. Marmax the general, on the other hand, though he fights the religious war and oversaw the atrocities we see, does have a practical understanding of the war he fights: he appreciates the practicalities of war, and respects Xena’s command of the healing room, as a fellow professional. He’s capable of learning from experience, and his humanity shows through as he watches both Xena and Gabrielle getting real results in uncompromising fashion.

He fights against Galen and the Thessalians in the name of freedom, and while he’s their prisoner, he explains that his quest for freedom justifies his atrocities. The equation starts to change for him, however, when Gabrielle tells him a story about freedom: the myth of the hunter Acteon, punished by the goddess Artemis by being turned into a deer and torn apart by his own dogs. Except she changes the story: instead of being torn apart, he learns compassion and peace as a deer—in other words, he learns to see the world through the eyes of those he was trying to kill. Marmax smiles indulgently when he hears this version, telling Gabrielle “It’s a pretty story. Too bad it has nothing to do with real life.”

Marmax actually hears two version of the Acteon myth: the second version is not a pretty story, told by Ephiny as she’s about to give birth to a centaur, but it is a tragic, all-too-real version of the Acteon myth. Her husband, a centaur, is in effect a combination of man and animal, like Acteon became. And like Acteon gazing on Artemis, he did what was forbidden to his race: he fell in love with an Amazon. Both he and Ephiny learned the lesson of compassion, but he was to suffer Acteon’s fate anyway: to be torn apart by the dogs of Mitoans, as they laughed. Marmax is stunned, and begins to see himself from his victim’s eyes at last.

Who is LIberius?

There is no Liberius in Greek myth; it’s a Roman name, and the closest Roman god to this name is the God Liber, the Roman Dionysus.

I had mentioned that one of the themes of this episode was freedom. On Xena Warrior Princess, the concept of freedom is usually associated with Dionysus. The god makes a presence here, in the form of Acteon himself! In Gabrielle’s version of the myth, she substitutes the name of Liberius for Acteon. Liber is not only the Roman name for Dionysus, it’s the root word for Liberty, and can be found in Ovid, in his telling of the story of the Bacchae. The main character of The Bacchae story (also Euripides’ final play) is The Stranger (in Greek, a female stranger is “xena”—Lucy Lawless has said this was the meaning of her character’s name).

There are numerous instances throughout the series where a character is named or renamed after a word signifying Dionysus. We can see this in Altered States: the character of Abraham is renamed Anteus, which, according to Robert Graves (The Greek Myths, ch. 85), is the surname of Dionysus in his sacrificial aspect. The myth of Narcissus and his death by dagger, according to Graves, was actually based on a Dionysiac ritual. Since Altared States is about sacrifice by dagger, it’s an appropriate name. Another example is Xena’s daughter, Eve. In the original drafts, her character Livia was originally named Lydia. The very first thing we see, in Euripides’ The Bacchae, is Dionysus introducing himself to the audience as the Stranger From Lydia. The name Eve very likely comes from the same play, as well as from another big influence from the show, Aristophanes. Dionysus’s worshippers in the play The Women’s Festival sing of “Evius, Evivus, Evoe,” the bacchae’s names for Dionysus, and sounding very much like Xena calling her baby “Evie”. Like mother, like daughter, they are both “xena,” the Stranger.

How do Centaurs procreate?

Xena Warrior Business wondered about the mechanics of centaur/human procreation, and whether Ephiny was the first human to give birth to a centaur. The Dan Scrolls author Dan Cassino mentioned that even in ancient Greece the idea of a centaur was not taken seriously as a literal idea, given the impracticality of a human-horse hybrid baby being a viable creature, and of course, Xena goes ahead and embraces the most impossible aspect of this myth! That said, longtime fans will remember Steven Sears’ explanation back in the day for how centaurs procreated on the show: briefly, all centaurs on the show were male because of a dominant gene (I don’t remember all the genetic mechanics he mentioned, but they were quite involved), and because there were no female centaurs, they naturally mated with female humans. However, Ephiny would be the first *Amazon* to give birth to a centaur, given their rivalry as described in Hooves and Harlots.

What I find most revealing about Sears’ explanation of centaur procreation, which was his own rationalization, is not its details, but that he gave this explanation during the run of the show, and after he had left it, not having watched any episodes made since he left (for all I know, this is still the case). In other words, he was confident that there are indeed no female centaurs, and knew he wouldn’t be contradicted by a show that the fans were watching, but he wasn’t. This tells me that the staff were instructed that male-only centaurs were an established rule. This raises a big question: Why? Wouldn’t it be dramatic enough to have a Centaur-Amazon relationship, even with female centaurs in existence? Wouldn’t it in fact provide even more dramatic tension? Obviously there’s no biological need to come up with such a reason, especially a show that had its own unique take on the myths. But they clearly felt it was important to establish this early on, well before the first season of Xena. So what aesthetic logic is this male-only centaur concept based on? To answer this, we turn to this episode’s chief cinematic inspiration.

Walking and Talking with RedBeard

Xena Warrior Podcast noted that there were similarities between certain scenes in this episode and The West Wing, in which the characters would have a “walk and talk” (i.e., conversational plot exposition while the characters walk through the scene they’re talking about). They also read off a quote by the episode’s director, T.J. Scott, how he wanted to emulate the realism of the medical drama E.R.

Now, E.R. certainly had a lot of “walk and talks”, but it’s very likely that in this case, Xena really did do it first, since it was conceived in 1993, before E.R. aired. What did it do? It drew its inspiration from the same place that Michael Crichton probably did: the Akira Kurosawa film, Redbeard.

The majority, if not the entirety, of Xena’s episode have some kind of Greek myth tie-in, but equally, they have some kind of cinematic tie-in as well. It’s already well known that James Cameron’s The Abyss influenced Gabrielle’s resuscitation scene. But the film references don’t end there. If I’m certain of anything, it’s that RedBeard was a model for Xena Warrior Princess: not just this episode, but the entire series. It’s the one cinematic source that I believe is required viewing for Xena fans. Rob Tapert never mentioned it, as far as I know, and I’d never seen it myself until well after I finished watching Xena. So how did I deduce this? While watching the series finale, A Friend in Need, and listening to its commentary, it was clear there were a number of Asian film influences that Rob Tapert paid homage to in return for the inspiration he drew from them: among others, the Chinese Ghost Story trilogy and Snow Falling On Cedars, about the Japanese internment during World War II.

I became curious about the character Akemi: was her name some kind of homage as well? I searched IMDb for Akemi, and came across Akemi Negishi, who starred in a wide range of Japanese films—one of them, Lady Snowblood, seemed very promising: it inspired Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill. But there wasn’t anything about it that really struck me as being uniquely inspiring to Xena. However, after reading an article in which Hudson Leick named RedBeard as her favorite film, which starred Akemi Negishi (one of Akira Kurosawa’s favorite actresses), I decided to give it a look. I was immediately struck by the obvious influence it had on Xena Warrior Princess. For a show that wears its film references on its sleeve, it should come as no surprise that there’s a film that inspires the series as a whole.

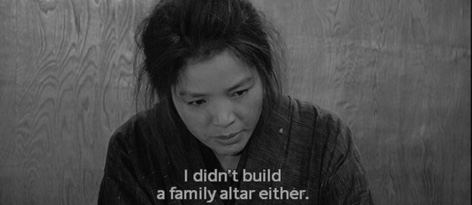

Akemi Negishi, as Okuni, forced to marry a man who destroyed her family

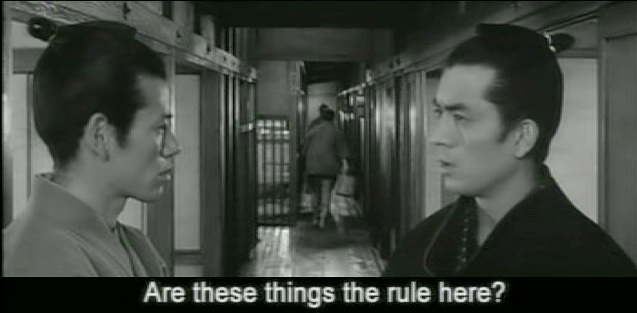

The original title of A Friend in Need was to be Mentors, and its the theme of RedBeard as well. The final scene of RedBeard clearly influenced the final scene of Sins of the Past, and with the appearance of Akemi in the series finale, this film reference comes full circle. The relationship of the fierce, samurai-like doctor, RedBeard, and his intern who has big ambitions to become a well-regarded doctor to wealthy patrons, but learns compassion while serving the needs of the city’s poor, mirrors the relationship of Xena and Gabrielle. The intern is introduced to life in a clinic when he’s given a “walk and talk” through its hallways, as it slowly dawns on him the challenge he faces:

The film is a series of stories, much like in a medical drama, about the physical and psychological challenges of their patients. The doctors need to understand both in order to heal them. There’s two such patients who tie the film together: Otoyo, the poor young orphan girl who’s being raised in a brothel, and Chobo, a boy thief that she befriends. Otoyo is difficult to reach at first, given her abandonment to a brothel at a young age. She dares everyone she meets to give up and abandon her, since she believes they will eventually anyway. The young intern indeed wants to give up after Otoyo keeps throwing her bowl of gruel at him, but RedBeard teaches him the secret: patience and unconditional forgiveness, no matter how many times she pushes him away. When Otoyo finally displays her first act of gratitude to the intern, he understands at last, and begs her forgiveness:

Xena Warrior Podcast made an excellent point during their coverage of Livia, Xena’s daughter: “Forgive me” is the show’s recurring note, and unconditional acceptance and forgiveness, its healing power. We can see many examples of it, in addition to Xena and Gabrielle’s own relationship (their own rift is healed in The Bitter Suite to the words “Forgive me”).

We see a close parallel to RedBeard in Forgiven: the young girl, Tara, wanting to become Xena’s “intern,” seeks acceptance, but can’t help provoking Gabrielle. She seems impossible to forgive, and Gabrielle, like Redbeard’s intern, sees no point in doing so, but Xena knows better: she was once that incorrigible, and knows how valuable genuine acceptance is. Like Redbeard, she shows patience and confidence in Tara, until it overcomes Tara’s lifetime of rejection and abandonment.

We’ll see a similar story of forgiveness, told in a very different way, in season five’s Little Problems, The Acteon myth is also present here, in a sense. The idea of learning compassion by becoming something else is seen when Xena, about to become a mother for the first time since Solon, whom she never raised, finds herself in the form of a little girl, Daphne. Daphne blames herself for her mother’s death, and assumes her father does too. Xena grew up in similar circumstances: she’s able to help Daphne forgive herself, and in turn, accept the difficult emotions of her own growing up.

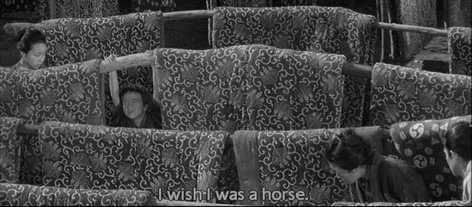

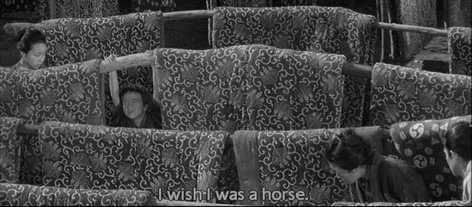

Chobo the boy thief is also difficult to reach, at first: when he meets Otoyo, he declares he wants to be a horse. Here we have the secret cinematic origin of the centaurs and the amazons, in the form of a boy horse and a girl “harlot”:

We can see how this would influence Hooves and Harlots: the Amazons, called “harlots”, are represented here by Otoyo, the girl from the brothel, and the Hooves are represented here by Chobo, the boy who wishes he was a horse. Queen Melosa complains the centaurs want the Amazons hunting grounds; like Chobo, who steals food from the clinic, they are merely thieves in their eyes.

Otoyo takes pity on him, having learned compassion from RedBeard and the intern, and when Chobo gets sick, and shames his family, Otoyo shouts his name into a well, to call his soul back to life. She and the kitchen cooks scream “Chobo! Chobo!” until it seems to work, as Chobo recovers. Here, then, is the connection between Hooves and Harlots and Is There a Doctor in the House. We can see clues in this episode: Gabrielle is injured while looking for a little boy, Piraeus, and Xena must find a way to call her soul back to her body. It makes aesthetic sense, then to have Ephiny return to this episode in need of medical help, pregnant with a centaur. And Xena is also a fellow “Harlot”, having been called that name by Galen.

This RedBeard influence doesn’t begin with these episodes, or Sins of the Past. The first clear reference to it is nearly a year earlier, on the third episode of Hercules, The Road to Calydon. In that episode, we meet two orphans: Jana, a girl raised in a brothel (!) and Ixion, a boy named after a centaur (!). A clearer parallel to RedBeard couldn’t be found! Their story involves a healing that’s very similar to Otoyo’s in RedBeard, and has Jana calling his name like Otoyo calls Chobo’s into the well.

By the way, does the name “Chobo” ring a bell? In Hooves and Harlots, Xena chooses “Chobo sticks” to fight the Amazon queen. Now, I’m well aware of the story behind how these were named: Steve Sears says he was writing that scene when, stumped for a weapon name, looked out a window and saw someone with a churro stick, and somehow “chobo” popped into his head as a good placeholder name, until something better could be thought of. I’ve no doubt that story is true, but I’m fairly certain that RedBeard was recommended viewing by Rob for the staff, and my belief is that Steve watched it (along with tons of other reference material), forgot the name, then channelled it again when he saw the churro. It felt right to him, and to everyone else who watched the film, naturally, so it stayed in.

Once Upon a Time in China

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that this episode is about a religious war, but that we only see one side of it: the worship of Ascleplius. We do get a glimpse of what this war could be about, though, when we see the conflict between Galen,the priest of Asclepius, and Xena, about proper healing methods. Galen believes healing is the result of his intercession with Ascleplius, while Xena relies on her actual experience healing injuries on the battlefield. Galen isn’t entirely deluded about the limitations of her methods , by the way. At one point, Xena loses a patient; and Galen points out her medical skills alone can’t solve everything, something that weighs heavily on Xena’s mind, and will need to confront in the final scenes of this episode.

Both podcasts list the healing techniques she employs as examples of her inventing new medical techniques, but I’m not so sure. Remember, we’re in a temple that forbids this kind of healing, so it’s all new to them, but probably not to anyone else (though obviously Xena is more proficient at it than anyone else). Galen describes her methods as “antiquated” and “impure”. “Impure” we can understand, if he believes that only prayer is effective, but “antiquated”? In other words, he seems to be aware of her approach, but considers it inferior. Does the word “antiquated” strike anyone as an odd choice, though? An odd turn of phrase like that makes me curious why they thought of it, and I believe this is another film reference, to the Once Upon a Time in China series in the 90s, starring Jet Li. The films explores 19th century China after opening up to the west, and the cultural clashes between Chinese traditions and western technology. The second film deals with western medicine and Chinese acupuncture. There’s a great deal of competition between the two, which is put aside during a battle, when a western-trained doctor runs out of anesthesia and calls in the acupuncturist who’s been banned by the hospital for his antiquated ways, in order to help remove the patients’ pain using his needles. The two doctors work side by side quite effectively, augmenting each others’ skills:

Xena also uses a kind of acupuncture in this episode, when she employs her pinch to numb the patient while removing his leg. This is also another connection to RedBeard: we don’t know the details of RedBeard’s tough background, but we get a sense of it when he visits the brothel to treat the orphan girl Otoyo. He’s confronted by the pimps who don’t like him taking their girl away, and he responds with highly efficient and clinical blows, doing as little harm as possible, including using a pinch to disable a man, then undoing the pinch and letting him go after he’s subdued. We’ll see a similar scene in this episode, when Galen calls in the temple guards to apprehend Xena, and she fights them off while operating on a patient!

RedBeard is not the source for Xena’s pinch (it’s taken from the Swordsman series starring the original inspiration for Xena, Brigitte Lin), but its medical applications, as part of treating patients and finding a way around killing people, is likely taken from RedBeard.

The sources I mention here are used in the series as motifs, and in one form or another can be found in other episodes.