During the six year run of Xena and Hercules, there were a number of unpredictable events in real life that seemed as if they threatened to derail the shows from their original purpose. I think their impact has been exaggerated, since they only seem to have postponed or shifted the schedules. One event did help drive the darker turn Xena took in the second season, though the reasons for that turn went undetected at the time; it didn't change the basic nature of the show, however; it reinforced it. That event was the cancellation of American Gothic, a one-season series by Sam Raimi and Rob Tapert, along with creator Shaun Cassidy and producer David Eick. It ran concurrently with "Xena" during its first season (and Hercules' second season), and was the most critically acclaimed of the three shows. Unlike the other two, it seemed to stand alone, without the great overlap of stars or staff the other two shows enjoyed, beyond the producers and composer Joe LoDuca. In terms of concept, however, there seemed to be common ground. Elements from The Bacchae that were suitable for the gothic storyline took center stage here: they weren't disguised, as they were on Xena, or relegated to villain-of-the-week status, as they were on Hercules. The villain of American Gothic was also its star: Trinity, a small town in South Carolina, was single-handedly run to the smallest detail by its sheriff, Caleb Buck, who was, quite literally, the devil himself. The town was his chessboard, the current staging ground for his ageless assault on mankind, and against him, the good guys rarely won: they were lucky if they could force him to a draw. That's because the sheriff represented a force that couldn't be vanquished in a single episode, or a lifetime. He was the dark side of man that couldn't be destroyed, only reckoned with.

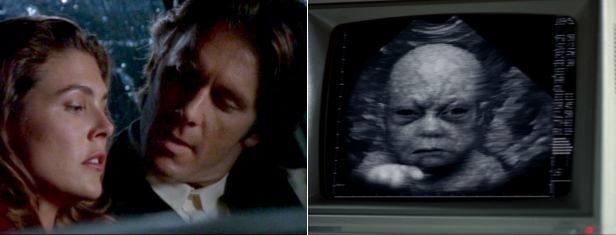

There's an important difference in the characters, however: Sheriff Buck is the evil mentor in ascendancy, a true psychological power to be reckoned with; Ares as a serious mentor came and went before Xena began, and as menacing as he appears, in practical terms he is closer to Silenus the satyr than the evil Stranger.01 Like Silenus, the former tutor of Dionysus whose powers have been eclipsed long before, Ares is the discredited teacher trying to regain his authority without success (both Dionysus and Silenus are associated with the ram, according to Graves). There is a deliberate comic tone to his scenes with Xena, and many of his other scenes set in Olympus are some of the best comedy on either show: alongside Strife and Discord, he's like Moe of the Three Stooges. We're not meant to seriously wrestle with his arguments, as we are with the Sheriff, and much of Ares' power comes from his alliances with greater Dionysiac/matriarchal forces: Callisto, Dahok, Hope, Alti, the Furies, the Fates...they're all more formidable than he is, when it comes to Xena, and it's no surprise in the final season of the show when losing his immortality doesn't seem to change him; it only seems to accent his qualities. As a shirtless farmer in Old Ares Had A Farm, and a beer-foam-bearded, lovelorn drunk in You Are There, he finally approaches the hirsute half-man, half-goat satyr nature that he always projected. It's no wonder Xena restores his immortality when she gets the chance: he represents an eternal archtype, and is one of the most appealing characters on either show: besides, you can't finish a Greek trilogy without Dionysus and Silenus. As I said before, nothing appears on Xena and Hercules only once, and early on during American Gothic's run, the producers were told their show would not be picked up for a second season, due to a change in leadership at the studio. This gave them the opportunity to finish the season with completed storylines, and more importantly, to immediately take whatever ideas left unfinished to other continuing projects. For Rob Tapert, that surely meant transferring the story of Rosemary's Baby, and the seduction of evil, to Xena, in the form of Ares. The god of war had only appeared on Xena once before word of American Gothic's impending cancellation was received, and he would be the logical choice to inherit the role of Dionysiac seducer (something the disembodied Dahok couldn't perform). His appearance in season one as lover, mentor and father would continue, and he would eventually inherit Sheriff Buck's wish to have a prodigy that could lead his armies on earth. Ares was Hercules rival and would play a bigger role in its next season, but because of the influx of discarded concepts from American Gothic, Ares would increase his presence on Xena during season two as a Dionysiac charmer: in Intimate Stranger, he works alongside Callisto, the Bacchic double of Xena, to get inside her head (literally), and in The Xena Scrolls, we're told of his special bond with Xena. On the spin-off, Young Hercules, Kevin Smith even plays both Ares and Bacchus. He never has the prominence that Sheriff Buck enjoyed on American Gothic, nor does he ever have the Sheriff's luck in impregnating his heroines with the devil's seed (that honor would go to Dahok and Callisto), but such was never meant to be, anyway: in this show, Xena is the Dionysiac hero, and stands between Hercules with his heroic defense of freedom, and American Gothic's necessity of evil; her heroism comes from her ability to face the reality of her own darkness and transcend it. The cyclops returns to Xena early on in season two, in The Giant Killer, which seems to pick up from Altared States in its Old Testament setting (and which will conclude in A Day in the Life). It opens with Xena and Gabrielle walking through a cyclops' graveyard: they don't bury their bones, as a sign of honor. This scene is taken from The Greek Myths,' chapter 35, "The Giants Revolt." In the myth, the giants led an assault on Olympus to free the imprisoned Titans. Silenus the satyr and Dionysus his pupil joined in to help defend Olympus, with Silenus providing the comic relief. The giants were buried in the earth, but their bones are occasionally unearthed by farmers. According to Graves, these are actually mammoth bones the ancient Greeks uncovered, so the unburied bones on The Giant Killer are a visual pun, combining the mammoths mistaken with giants, and the legendary elephants' graveyard. The story's religious elements relate to the giants as symbolic of nightmares and murderous inclinations, which can be cured by the proper herbal rites. The lightning bolt reference ties this episode loosely to the myth of Zagreus (an alternate form of Dionysus), which we'll see in A Day in the Life, a satyr play sequel to this episode. The nightmare of the myth is embodied by Goliath's recurring nightmare of losing his family to a rival giant, and the murderous inclination of the myth is his daily reality. His hatred leads him towards reckless vengeance, which Xena tries to warn him away from: "No, you're blind with hatred." The cyclops-related theme of blindness announces itself, and there's also a clever reference to the sheep of The Cyclops when David (the slingshot wielder) recites his famous psalm: "The Lord is my shepherd." Goliath won't let himself be taken down like his brother in The Cyclops, so he wears a protective helmet: he's not a cyclops, of course, but we're told that giants are vulnerable in the same area where a cyclops eye would be, making him the dramatic equivalent of Euripides' giant. Xena tricks him by finding another way to blind him: using the soldiers' reflective shields to shine the sun's ray's in his eyes, allowing David to hurl his slingshot. Using beams of light to blind the "cyclops" has its basis in The Greek Myths as well: chapter 170, note 3 tells us that the cyclops' eye was a solar emblem. We'll see this concept used again many times, including later on this season on both Xena and Hercules. David's wife-to-be in this episode is not Bathsheba, but Sarah, which is not biblically correct: Sarah was Abraham's wife, so she should have been in Altared States as Anteus's wife; her character there was simply referred to as "mother," allowing her name to do double duty here in the episode's sequel. Sarah's presence here (just as her implied presence in Altared States) recalls Serafina, the friend of Eurydice, and the themes from Black Orpheus, except that Xena does not lose her soulmate, but just a good friend that she has no choice but to help kill. An eternal story, the divisions war creates are the hardest to bury. The significant contribution of The Giant Killer is to continue the theme of the One God supplanting the ancient pantheons begun in season one's Altered States. This explains why those two episodes were given biblical, not Greek, settings: they're meant to conjure in our minds a specific "One God", of the Old Testament, and later, the New Testament. This is most likely a deliberate misdirection from the top: Rob Tapert has said the Twilight-of-the-Greek-gods storyline was intended to be a Hercules arc, but Xena's involvement would arise from her Rosemary's Baby story beginning in season three, borrowed from American Gothic. Since the demise of "American Gothic" would have been known before Altered States was made, the Rosemary's Baby arc could very well be the first importation from the cancelled show, and the first seed could have been sowed in this episode, since that's the first mention of the One God. The misdirection involves leading the audience to regard any mention of the "One God" as the biblical God. As Xena and Gabrielle initially associate themselves with this One God, the audience in turn associates the One God of love, salvation and redemption with them, so when the Rosemary's Baby arc opens season three with the arrival of another "One God", the audience is in for quite a surprise! This surprise didn't come out of nowhere, though; it's the "prestige" for nearly two seasons of sleight-of-hand.02 |